THE HOUR OF DARKNESS

How do we express our morality in the ferment of war and bear witness to God?

A favourite military aphorism, that no battle plan survives first contact with the enemy, implies the difficulty we have in controlling the outcome of conflict. There may be strategic aims, but war takes its own malevolent course and the struggle to arrive at the goals we have set means it can be prolonged and cause great suffering.

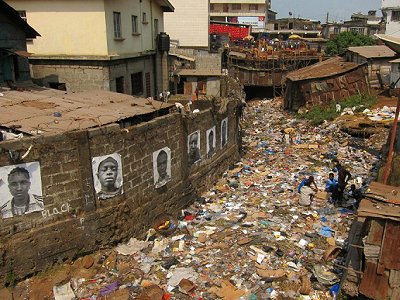

Any discussion around the justness of war has to begin with a humble observation. When we speak of justice in war, most of us do so from an abstract, philosophical position. Those who have personal experience of war, especially civilians caught up in its fury, would find it hard to locate much justice or limitation in its prosecution. There are many places in this world where no effort is made to surround warfare with moral parameters and the intention is to cause profound injustice and anguish. The enduring civil war in eastern Congo has been fuelled by reciprocal atrocities, including the systematic rape of women, which creates an unforgiving climate for resolution.

Just war theory has ancient pedigree, being a meshing of religious and philosophical traditions. It is significant that western political leaders often feel the need to refer to it to justify military action. While some are sceptical of this recourse, we should be glad of it, for it demonstrates a need to surround conflict with as close to an ethical framework as it is possible to get when you are trying to kill other people.

In essence the principles of just war are that there must be a just cause; it should be waged by a proper authority; be proportionate; undertaken where there is a reasonable chance of success; and as a last resort in the pursuit of peace. These are admirable tenets that are qualified by the subjective way they are often applied. At the time we may seem to pass the test, but the cruelty of war and the verdict of history may suggest otherwise. I suspect that some forms of modern warfare deserve a further test: that where fragile nations are subjected to outside intervention, there should be a willing and credible commitment to nation building, to ensure the second state of the nation is not worse than the first.

There is much scholarly and journalistic debate about the causes and justification for the First World War, but few people could argue today that it properly passed the criteria of just war, especially with its appalling waste of human life. Even manifestly just causes like the allied resistance of Nazi Germany, which was a fight to the death for the soul of Western civilisation, failed to meet all the principles of just war at all times. Not every battle was conducted in a proportionate manner, suggesting that even the most moral and courageous of wars are stained by injustices against civilians.

Ours is a vastly different context a hundred years on from the First World War and our moral commitment as Christians to the welfare of society is to debate where the challenges lie today and how we can do our best to ensure war is conducted as a last resort in the cause of peace. In the post- Cold War era, there has been a new emphasis on humanitarian warfare, which is conducted against a nation or a faction within it by other nations in order to protect vulnerable indigenous peoples. At first, in the wars of the former Yugoslavia, there was a reluctance to intervene on one side against another, though history strongly suggests this was a war of Serbian expansion against other ethnicities.

The genocide in Rwanda twenty years ago changed everything. While outside powers debated whether the atrocities amounted to the legal definition of a genocide which would trigger intervention, 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis were massacred. A new resolve was subsequently found to prosecute wars against Serbia over Kosovo and against the Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone. On most criteria, these interventions were successful; Britain’s reputation remains especially high in Sierra Leone thanks to the bravery of a relatively small number of British soldiers.

Since the turn of the century, the context for humanitarian intervention has become muddier, culminating in the civil war in Syria. As an ancient civilisation systematically destroys itself, few argue for armed intervention; the experience of the war in Iraq and the likelihood of being resented and shot at by all sides figures highly in the calculations. We have consciously restricted ourselves to humanitarian relief, even though Syrian civilians have suffered as much as any people in living memory. Politicians have to make fiendishly difficult decisions which may be made in all good conscience but which may not stand the test of time. It is easy for the rest of us to judge those who make messy decisions on our behalf; we should rather be praying they find wisdom from God, because the lives of many people are in their hands.

The conflicts of the post-Cold War era have been poisoned by some shocking atrocities, but this does not mean the victims must always be deprived of justice. The creation of an International Criminal Court in The Hague demonstrates to war criminals that there may be an accounting for their cruelty. The court may be slow and impenetrable in its processes, but it is a necessary indication that when civilians are deliberately targeted in war, the guilty will now be held to account.

Loving our enemies does not mean that we have to like them but it does mean we should try to surround our contact with them in as moral a framework as we can sustain in this messy world, to ensure our own consciences are not condemned, that innocent people can live without fear and that our enemies will be dealt with justly and in keeping with the expectations God has of us, whether we believe in him or not.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?